Learn

Johanna van Gogh-Bonger and Expedition Behavior

How Jo’s quiet stewardship of Vincent van Gogh’s art and letters models the servant leadership of expedition behavior.

Johanna’s Mission and Cultural Legacy

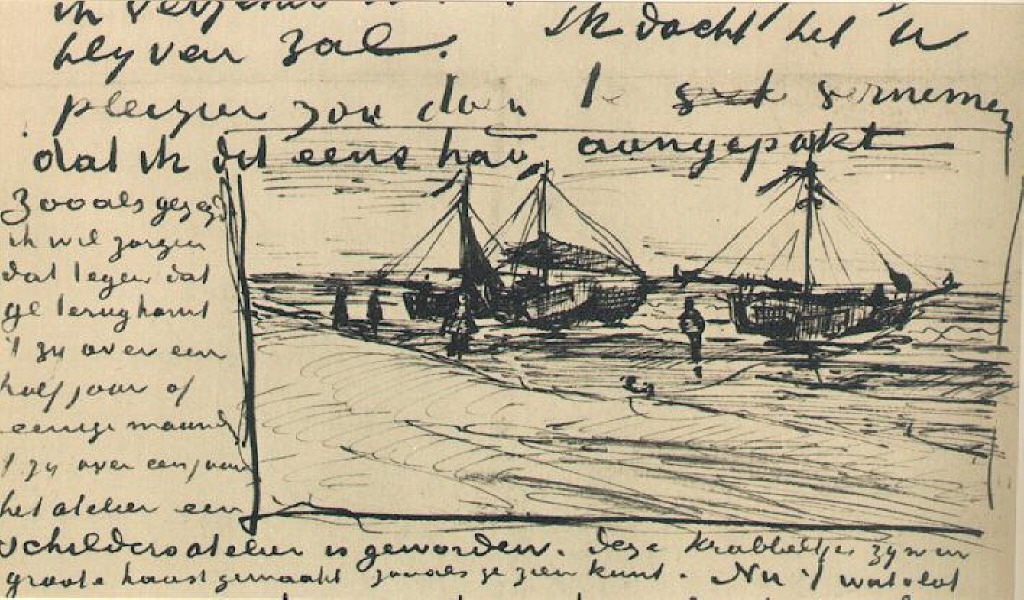

Johanna (Jo) van Gogh-Bonger (1862–1925) inherited hundreds of Vincent van Gogh’s paintings and letters after the deaths of Vincent and her husband Theo in 1890. At the time, Vincent’s work was little valued. Jo devoted herself to preserving, organizing, publishing and exhibiting the paintings and correspondence — often using her own money and time — so that Vincent’s art could be understood and appreciated by the public. Her long-term stewardship laid the foundation for the Van Gogh Museum and the artist’s posthumous fame. Van Gogh Museum: “The Woman Who Made Vincent Famous”.

For primary documents and letters Jo worked on, see the edited correspondence at the Van Gogh Letters project: Van Gogh Letters (example: Jo’s letters), and translations hosted at WebExhibits: WebExhibits: Jo van Gogh-Bonger (1914 preface/translations). A recent overview of Jo’s role in art history is covered by Artnet News’s reporting on museum shows: Artnet: Jo van Gogh-Bonger exhibition.

Expedition Leadership Values

“Expedition behavior” is a leadership concept institutionalized by the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS), originally inspired by Paul Petzoldt. It emphasizes service to the mission, concern for others, dignity and respect, and doing your share (plus a little extra). See NOLS’s definition and principles here: NOLS — Expedition Behavior.

NASA astronaut Reid Wiseman — who experienced NOLS training — described expedition behavior in practice from orbit, praising the small, often unseen acts (for example, a crewmate who always empties a full trash bag) that sustain morale and mission success: NOLS Blog — “Astronaut Reid Wiseman on Expedition Behavior”.

Connecting Jo’s Work to Expedition Behavior

Serve the mission: Jo invested time and money in framing, cataloging, lending, and promoting Vincent’s paintings because she believed the artist’s work should be shared. Her choices were driven by the mission of making Vincent understood, not by personal publicity. (See the Van Gogh Museum essay above.)

Care for others: Jo treated Vincent’s paintings and letters as a cultural trust she protected for future audiences. She published the letters so readers could hear Vincent’s own voice and learn his artistic purpose — a classic example of serving a larger group good over private hoarding of cultural assets. See examples in the Van Gogh Letters project and WebExhibits resources linked above.

Step up quietly: Much of Jo’s work was unglamorous: cataloguing, corresponding with dealers, arranging loans, and translating letters. These small, persistent actions mirror the “do the little things” ethic Reid Wiseman praised in his NOLS reflections.

Group-focused decision making: Jo sometimes consented to sell or lend treasured works when doing so would place Vincent’s paintings before influential audiences — a strategic trade-off in service of the collective goal of public recognition. This mirrors the expedition mindset of prioritizing the expedition’s aims over individual attachment.

Why Jo’s Example Matters

Johanna van Gogh-Bonger shows how quiet, persistent, purpose-driven leadership can reshape culture. Her choices obey the rules of expedition behavior: she served a mission that transcended personal reward, cared for a cultural “team” (Vincent’s art and future audiences), and persisted through years of rejection. The result was not immediate fame but a durable legacy that benefited generations.